08. You Know Who Had an Arc? Noah.

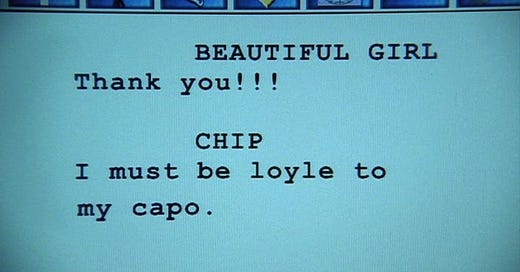

“Why would there be two antichrists? There’s only one Christ!”

One of the funniest, most tragic moments in the entire run of The Sopranos is when Christopher searches for his name in newspaper coverage of an FBI sting, finds it, then steals every remaining copy of it for posterity. It’s a perfect, hilarious encapsulation of what a tremendous moron he is, but it’s also a harsh look at how pathetic and futile it is for any of us to crave recognition above all else, to prioritize external validation above internal growth. Wanting to be seen in a particular light is a logical consequence of being a person in a society, but it requires so much fixation upon forces beyond our control. And the wider the gulf between the person you want others to see and the way you actually behave, the more alienated you become from the possibility of genuine intimacy with people who might know you as you are. In short, the way we obsess over public image is often an attempt to mitigate loneliness that only creates more of it, leaving us, like Christopher, grasping at whatever scraps of attention we can find.

That focus on the discrepancy between one’s public identity and private self doesn’t just complicate our understanding of Christopher; it also makes this the most effective of the show’s episodes that deal explicitly with Italian-Americanness. (That being said, I’d argue that many episodes that handle that implicitly have far more interesting things to say about it.) Compared to “Commendatori” or the dreaded “Christopher,” “The Legend of Tennessee Moltisanti” is intensely watchable, even during its on-the-nose dialogue about harmful stereotypes and Italian contributions to society.

And that’s probably because this episode is a response to cultural discourse that pre-dates the series, where the others are defensive metacommentaries about certain viewers’ responses to it. But I think a big part of its comparative watchability is that it’s less monolithic in its handling of Italian-Americanness. Its explicit discussions about Italian culture, though certainly not the show’s best dialogue, don’t just laundry-list things; they dissect how people’s definitions of Italian identity do and do not shift in relationship to their class, as well as how many generations removed they are from the immigrant experience. And, the episode is deft at articulating these anxieties as a gendered phenomenon. As in the world at large, group belonging is defined here by the experiences of men — men who, no matter how good and/or progressive they believe themselves to be, are oblivious to the limitations of their points of view.

But mostly, I’d argue that the episode works better than those others because it draws clearer parallels between cultural and individual insecurities. Each storyline uses larger questions about identity as a way in to capturing how individual characters — individual men — understand themselves in relationship to one another and to their contexts, and shows us how that self-understanding is a far, far cry from the way they’d like to be seen by the world at large. It’s only appropriate, then, that Christopher is its star. (It’s also appropriate that it pays so much homage to Goodfellas, a movie in which 90% of the plot is driven by men doing colossally stupid things in an effort to assuage their senses of personal and ethno-religious inadequacy.)

Throughout the entire episode, Christopher follows his worst, most insecure instincts. We open the episode inside his nightmare — the first of only a handful of times we get to be inside a dream that isn’t Tony’s, and, like those other dreams, it’s all about guilt. (Most of Tony’s dreams are also about guilt, but some of them are just about horniness, or guilt about horniness. Truly, this is the most culturally Catholic text ever created.) But he refuses to face his dark night of the soul head-on. Instead, he demands constant screenplay feedback from Adriana, rejects Paulie’s goofy but well-meaning attempts at companionship, and assaults a bakery worker because he’s irritated that Tony treats him like an errand boy — an echo of Tony beating the shit out of Georgie because he’s annoyed with everything and everyone else in “46 Long.” He’s clearly depressed, so depressed he doesn’t seem to care at all about the possible fallout of the FBI sting, because at least it would break up “the fuckin’ regularness of everyday life.”

He laments his lack of direction to anyone who will listen, but rejects the empathy and advice they attempt to offer in response. It is, admittedly, flawed guidance, but at least it reflects some effort to connect with him. And when Tony offers him the chance to open up about his obvious sadness in more detail, Christopher shuts him down immediately. That argument/conversation between Christopher and Tony in the car is one of my favorites in the first season: it’s funny (James Gandolfini was as skilled at comic anger as he was at truly terrifying rage) but devastating, digestible and complex at the same time. The dialogue recycles earlier moments — Tony’s diagnosis of Christopher’s “cowboy-itis” echoes his “whatever happened to Gary Cooper?” lament; Christopher’s assertion that he’s “no mental midget” is the apotheosis of multiple characters’ articulations of mental illness as an embodied deficiency — but reveals new information to us as well.

It’s not fully clear before this argument that Tony’s terminal disappointment with Christopher comes from the fact that he genuinely cares about him, or that Christopher’s surliness with Tony comes from his admiration of him. Their conflicts emerge not just because they’re too dysfunctional to express any kind of genuine human emotion, but because they see the parts of themselves they’d like to hide in one another, and they shy away from shining any light on those things. Their care for one another can only stretch as far as the limits of their personal vulnerability — which means it goes, effectively, nowhere, and will only become more and more limited as their insecurities expand.

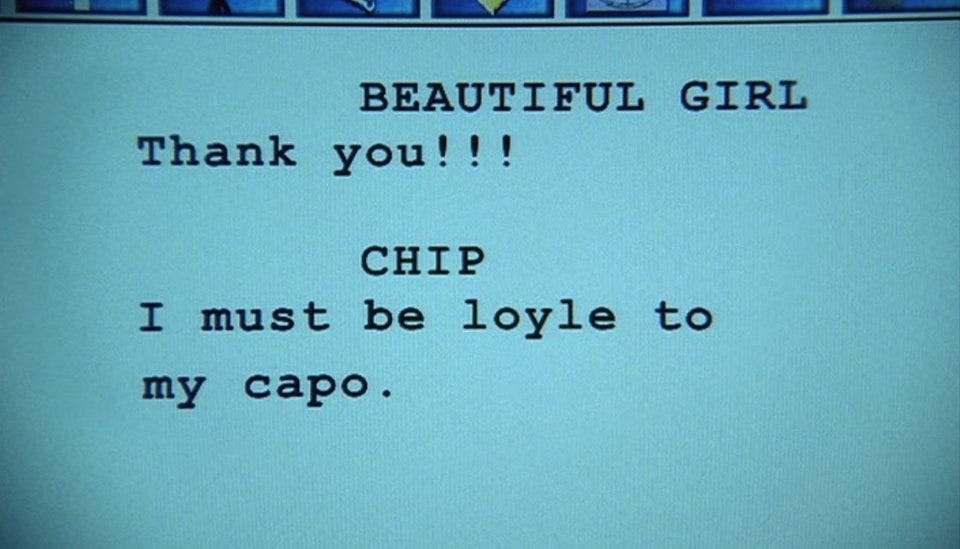

But despite all this repression, Tony clearly sees Christopher as a son-like figure — and that of course raises the question of whether Christopher, like Tony’s biological children, can escape his influence. On the one hand, he seems to want out of this life more desperately than anyone else, and he does make an effort to carve out a new path for himself (just not a particularly competent one.) But on the other hand, he doesn’t seem to want out for the right reasons: it’s not that he has outright moral reservations about his work, but that he’s resentful of its lack of prestige, angry about his contributions to it going unrecognized, and unwilling to interrogate whether his anger and resentment might be more complicated than they appear on the surface. He’s in crisis but he’s not, as they say in reality television parlance, here for the right reasons. It’s hard to imagine that a character who envies Keanu Reeves’s character arc in The Devil’s Advocate might be anything but doomed.